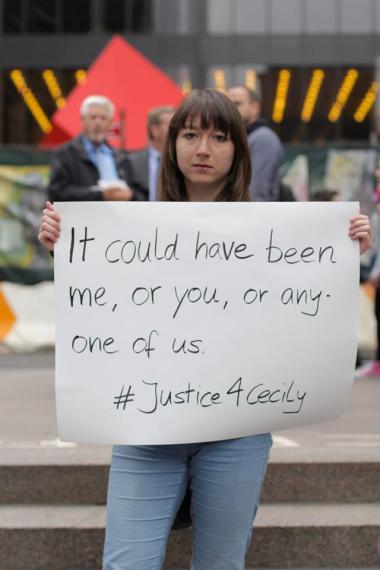

On Monday, Occupy Wall Street activist Cecily McMillan was sentenced to three months in jail and five years of probation, after she faced down a maximum sentence of seven years in prison for her conviction of assaulting a police officer. Her supporters, unsurprisingly, feel the sentencing is excessive – especially given her testimony that the officer in question first grabbed her breast – but it's also clearer than ever that McMillan's conviction will have a chilling effect on the future of serious activism.

A potential seven-year sentence, part of which likely would have been served on Riker's Island (with its notoriously dismal record on prisoner rights), serves as a message to would-be protesters: don't attempt to resist, or this could be you. It doesn't particularly matter that McMillan will now "only" be in Riker's for another 60 days (with time served). That prosecutors floated the idea of a seven-year term is enough to permanently terrify dissidents into avoiding confrontation with police – even if those "confrontations" come in the form of exercising your First Amendment rights.

The threat of Cecily McMillan's possible punishment may become her legacy, not that she "got off easy" or, saddest of all, that she stood up and got everyone to listen in the first place. Indeed, many Occupy activists who got the attention of the police have been silenced by an unfair justice system – and their stories may never be heard at all.

Protesters are much less likely to participate in collective action if they know they can be arrested for oftentimes specious reasons, detained for long periods of time and then inconvenienced for months – even years – before they see a day in court. McMillan may have been one of the last Occupiers facing trial, but she was by no means the only immediate victim of police violence targeting protesters.

During the height of Occupy Wall Street (OWS), I watched as activists were arrested for a slew of superficial reasons, including "blocking pedestrian traffic", a laughable offense to anyone who has ever tried to traverse New York City's naturally crowded sidewalks. And if protesters weren't arrested for standing on the sidewalk, the police frequently detained activists for standing elsewhere: I personally witnessed more than a few officers pull protesters and even journalists off sidewalks ... and then arrest them for standing in the streets.

After getting arrested for all those highly suspicious reasons, an Occupy protester – indeed, any protester – can languish in a holding cell without even being charged. If New York City – a lot of cities – later decide to press charges, a protester can look forward to months of being inconvenienced and called into court ... that is, if she could spare time off work, should she be lucky enough to be employed. It's no surprise so many activists take plea deals as opposed to suffering for months in a tangled court system.

Occupy was a bullseye for overzealous policing from the start. In an early public example from the movement's infancy, New York Times columnist Ginia Bellafante went to Zuccotti Park to observe the burgeoning group, and described a young man who stopped by Zuccotti only in "fits and spurts" because his mother feared he'd be tear-gassed by the police. She never followed up with him, but his mother wasn't entirely wrong: it was common to see the police bullying, intimidating and sometimes beating protesters.

The most famous example of this is probably NYPD deputy inspector Anthony Bologna, who pepper-sprayed peaceful female protesters during an OWS march. In 2013, the district attorney's office announced that it would not prosecute Bologna – and the NYPD docked him just ten vacation days and reassigned him to Staten Island.

McMillan, in part by refusing to accept a plea deal and going to trial, became the face of what many New Yorkers wanted to ignore: that police were able to destroy and discredit OWS with their brutal tactics and a constant media drumbeat that the protestors themselves were to blame for the violence inflicted upon them.

Many postmortem diatribes have been written about "why Occupy Wall Street failed", and most of these explorations are simply an excuse to punch some hippies, by claiming that protesters were too disorganized and scatterbrained to affect real change. But these stories usually fail to contend with the overwhelming police brutality endured by OWS protesters and how effective that violence was in discouraging supporters – and, ultimately, in forcing them to dissolve and reorganize into other groups tackling economic and social inequality one piece at a time.

During sentencing, Judge Ronald Zweibel remarked, "The court finds that a lengthy sentence would not serve the interests of justice in this case." Justice was not served to McMillan – but it wasn't served to the Occupy Wall Street protesters, either, nor to victims of police brutality at large, or, you know, to the millions of Americans who remain victims of Wall Street's corrupt practices.