Was Occupy Wall Street the brand new phenomenon many journos and academics have purported it to be? Does it matter? Well yes. Because all movements burst and then recede, and in the between-periods it's important to remember that resistance to rampant inequity, really never ceases. It's important because this memory helps us to keep the faith during dark days (when the media doesn't bother to cover our mobilizations), and to build energy for the next uprising.

Occupy Wall Street was inspired by the spontaneity of the uprising in Tunisia, the dogged spirit of Tahrir, and the Zapatista ethos. It sought to call out the unfinished business of the Civil Rights movement - resurrecting its long-tabled economic and racial justice fight, and recalling its culture of direct action. And it came of the same DNA as the Counter-globalization movement, which worked to raise brand-new questions about trade justice and the impact of globalization on workers, farmers and indigenous people. Occupy Wall Street brought together tools, networks, and messages developed by thousands of people over decades.

Here are some things the press and lots of academics credit Occupy Wall Street with introducing, plus a few they forgot:

1. Raising the issue of economic inequality

2. Reclaiming public space

3. Spreading the occupation tactic globally

4. The 'Sparkle” and People's Mic

5. Inviting everyday people to lead, by sharing their story

6. Drawing folks who'd never engaged in activism in their lives

7. Emboldening radical Labor activists

8. Bringing the fight “home” to Wall Street

We often get sole credit where it isn't due, and vice versa. Let's see which of these we deserve:

1. Raising the issue of economic inequality.

You know when you say something, and the person you're talking to acts like they didn't hear you? And so you reiterate your point, and -- as if you never uttered a word -- the other person just keeps doing what they were doing. A lot of time passes, and you start to wonder: “Should I repeat myself? Maybe I didn't say what I thought I said, maybe I didn't say anything, at all?”

You repeat and repeat yourself and they continue to ignore you and you start to feel a little crazy.

That's how many an activist has felt since the 1980s. The issue of economic inequality has never stopped being an issue – and activists have unrelentingly raised it. Of course, inequality today is the worst it's been since the Great Depression, but the counter-globalization movement foresaw it all, and warned us constantly through their own alternative-media channels. The mainstream press just wasn't interested at that time (maybe because until citizen-media significantly displaced the “official story” and destabilized the mainstream media's hegemonic grip, the media business was booming).

Did we introduce the issue of economic inequality to the media? Not in the slightest. But did we manage to introduce the issue into mainstream discourse, and generate a sustained conversation about it for the first time in many decades? Absolutely. With our frenetic 24-hour direct confrontation of Wall Street, we got the 99%, the 1%, and the politicians among them, to talk about inequality every day for months.

Not that all that rhetoric means they're really listening, but you know, it's kind of helpful to feel sane again.

It's now clear: the subject is sticking, as evidenced by increased talk about economic inequality by people at the “top”, two and a half years later.

2. Spreading 'Occupy' globally.

The proliferation of encampments globally, under a decentralized but unified banner, was certainly unprecedented. It's not clear how much we share, ideologically, with an Occupy Bangkok or Occupy Zurich; but what is clear is that for the first time, the United States is connected with global struggles all at once and simultaneously, and on common ground.

The Counter-globalization movement was probably the first to get regular mainstream press about American support for struggles abroad - the Zapatista struggle, the occupation of Tibet, the genocide in East Timor, the question of fair versus "free" trade, outsourcing and sweatshop labor. During the Counter-globalization movement, activists sought to highlight the common struggle between workers worldwide, but (right or wrong) they were viewed as altruistic and economically-secure activists acting in solidarity with oppressed people overseas as a matter of conscience. Today, it is understood that we Americans are all fighting for ourselves as much as for any oppressed people abroad.

3. Reclaiming public space.

A German friend of mine who studies urban planning recently complained that Occupy Wall Street is all the rage in academic circles right now. What's wrong with that, I asked, what are they saying about it? "Well," she explained, "they're all inserting a sentence or two into their abstracts crediting Occupy Wall Street with being the first movement to reclaim public space. It's perhaps a reflection of the dominance of American universities in academia. Because clearly, it was not the first.” I agreed with her, wholeheartedly.

As the American people seemingly sat around after the economic crash, Tahrir exploded into revolution, the Indignados' took back the Spanish "Squares", Greek workers engaged in one after the other factory occupations, and people in Israel erected tent cities all over the place. Meanwhile at the heart of Wall Street, the source of the global economic crisis, there were just a few tiny protests. You could say these uprisings kind of put the United States to shame.

Then, eight months before we occupied Liberty Square, the people of Wisconsin showed us up, through the one-month occupation of the State Capitol building in Madison.

Week after week, people had all their housing, clothing, medicine, food, books and companionship needs met, in the rotunda and the nooks and halls of the capitol. This wasn't the first long-term occupation in the United States, either. Going further back in American history, there were: the Hoovervilles of the Depression; MLK's Resurrection City, staked out on the White House lawn; the anti-war occupations of the 60s and the anti-sweatshop occupations of the 90s, on American campuses everywhere, etc etc.

To those deeply involved with Occupy Wall Street, it's extremely disturbing that so much radical history has been erased in the accounts of our movement. So many of us have spoken to countless journalists and graduate students and emphasized this point - but no matter how carefully we craft a quotable sound byte or try to tie it in with their thesis topic, somehow that context never makes it into the final copy. Media-makers and academics: We get it. Taking the time to situate Occupy Wall Street within a deep global context of ongoing struggle wouldn't have made you look as sexy; and we all want to look sexy.

4. The 'Sparkle” (Nah) and People's Mic (Nope).

Most of the people who stumbled upon Liberty Square had never seen or engaged in consensus process before. Thus many assumed that the “hand signals” used to smooth the consensus process, originated with Occupy Wall Street. But the sparkle, or "twinkle", or "silent clap" as it's also called, has been around on an ongoing basis for at least a century; it is still used every day in meetings around the country - especially in housing co-operatives and collectively-run businesses and community spaces. Meanwhile, the People's Mic (or human microphone) goes back to the No-Nukes movement of the 80s (which in turn also linked to the women's movement of the 70s), and was used again during the WTO protests beginning in 1999.

5. Inviting everyday people to lead, by sharing their stories.

During the occupation of Liberty Square, tens of thousands of people told their stories during assemblies, through self-created media channels, and to the mainstream press - and the testimonials of everyday people were featured on the news on a daily basis for weeks. As such, Occupy Wall Street didn't just get the issue of economic inequality into the news, we got the media to portray activist assemblies for the first time in many many years - and to portray activism in terms of public assembly by everyday people.

Occupy Wall Street introduced no sanctified leaders like a Ghandi or MLK, Malcolm or Mandela. Instead, humble role models proliferated everyday eloquence all over the place, and in doing so, gave others permission to do the same. Each of us could be a spokesperson, and while some handled this responsibility better than others, it continuously dawned on us:

This movement is running on stories.

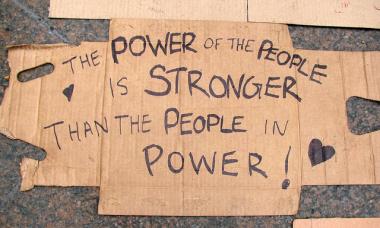

Every kind of story, of every kind of person, from every walk of life, was told in Liberty Square. Anyone could participate, express themselves directly - starting with a piece of discarded cardboard and an indelible marker.

We feel confident that because so many were emboldened to speak up loudly in 2011 and 2012, those who have not yet felt ready to take action in their own community, will be doing so in the coming years.

6. Drawing folks who'd never engaged in activism in their lives.

YES. We did do that. And we were a movement led by the unaffiliated.

Unlike the movements of the 60s, this wasn't a student-led movement. It wasn't a church-led movement. It wasn't a union-led movement. It also wasn't a movement led by any political party or network of NGOs. This meant we could not be dismissed as a bunch of bourgeoise students talking theory, out of touch with everyday realities; or cast as a mindless hoard sent their marching-orders from large-scale unions or parties; or construed as unusually altruistic-types assuaging their guilt through charitable work.

One of the things that distinguished progressives and radicals that participated in Occupy Wall Street, from those that didn't, was in fact that most of us were unaffiliated.

Many had few places to express our political opinions beyond the voting booth. Existing political and social justice institutions simply had not made us feel welcome, or empowered, or attracted our commitment. So we broke our alienation from the political arena and did our own thing, wholeheartedly, in a spirit of liberation and communion. No administrators or single figureheads were able to send "marching orders" to people on the street (and if they tried, little mutinies would occur just before or after an action). Whatever the critiques of the decision not to set a prescriptive agenda prior to launching Occupy Wall Street, brand-new, totally green activists got an amazing chance to help form the direction of the movement on a day-to-day basis. And whenever this happens, it is a truly amazing thing.

Some very significant folks were paid to be there by big unions and NGOs - but just a few. Who-knows-how-many infiltrators were paid by Republican thinktanks and the Democratic Party machine, but everyone else in NYC came representing their own interests. Oddly, lots of very active groups and individuals that you would think would have plunged right into this class-focused movement, came by the park just once or twice, and otherwise hung back. There were good and bad things about this. The bad thing is that many of the most experienced social justice pioneers out there, didn't offer up many or any of their skills. At the same time, the fact that the vast majority of institutional-left and even grassroots NGO professionals were no-shows for the biggest movement around economic justice since the 20s, also left us free from the ideological constraints imposed by their funders.

Occupy Wall Street also acted as an “activist factory” - which generated a new generation of leaders and united them with long-devoted activists, for the first time since the counter-globalization movement. We brought out hundreds of thousands of everyday people, across the country, who had never once before in their lives raised their voices in protest. These first-timers didn't necessarily participate over the long haul, but they got an important sense of what a mass movement can feel like. In a more lasting sense, Occupy Wall Street brought together and reactivated a splintered and dormant left, broke the isolation of devoted activists and led to new group formations such as Strike Debt, the Alternative Banking Working Group, Occupy the Pipeline, Tidal and this website, among others.

7. Emboldening radical Labor activists.

Some of the most committed activists in Occupy Wall Street were labor activists intent on occupying their unions before the occupation of Liberty Square ever began. They felt that institutional labor needed to move towards a more confrontational approach, employing more direct action tactics, forming nonunion associations modeled on the workers’ center movement, and organizing new emerging work sectors, such as fast food workers. Occupy Wall Street gave the labor movement a push – lending increased legitimacy to its more radical organizers and tendencies. And through constant direct action, we've seen serious wins by workers at fast food and big box chains and most recently, in the field of airplane maintenance.

8. Bringing the fight “home” to Wall Street.

Occupy Wall Street was not at all the first uprising at the heart of the capitol of capitalism. Most recently, CUNY students staged an Occupation right on Wall Street in the 90s; and at least one other long-term occupation precedes Occupy Wall Street, a 200-day homeless encampment in front of City Hall in 1988. Notably, the infamous anti-capitalist Yippies occupied Wall Street for a day in 1979, with a civil disobedience in front of the New York Stock Exchange involving 1,000 arrests. And in the 1960s, AIDS and housing rights advocates, feminists, environmental, and anti-Nuke activists converged on the Wall Street area at least once a decade.

Still, we may be the first to have maintained our confrontation of the banks, and rampant capitalism – at the heart of Wall Street – for so long. And today all but the 1% are now building on a new premise: that Wall Street, the banks, and unchecked capitalism, are at the root of countless connected grievances. What began as a conversation about economic inequality, has evolved into a genuine examination, at every level of society, of the role of banks in corrupting both our economy and democracy.

One last thought on reclaiming radical history

Why's it so important that we remember that Occupy emerged of many prior movements going back a hundred years, all of them in some way unresolved? We have so much to learn from the difficult decisions made by prior movements - especially around the politics of prioritizing one concern over another, and tabling key issues in the process. Just as importantly, looking back a bit helps us keep our work in perspective - especially as we take on the monumental behemoth which is capitalism.

After all, just as any movement started to take on the roots of rampant inequality, that movement was brutally repressed.

While it may be little solace, it's useful to stop bashing ourselves for "failing" to have ended inequality or “fixed” our broken economic system, yet.

And it's equally important that we remember that Occupy was more immediately preceded by decades of unrecognized work, by thoughtful people in the activism scene, union world, and NGO sector. Why? Because we need to pay attention to their absence. Some of them tried valiantly to get involved. But comparatively few of them dropped what they were doing — or rather redirected it — so as to lend their skills towards finessing the first big movement focused on class in a very long time.

We really should be asking ourselves, and them, why.

Some of these people tried to access Occupy Wall Street, but found it impossible to navigate the hot mess that was the assembly and the occupation. Many of the most experienced among them weren't used to serving an uncontrollable mass of people, and playing at times peripheral roles – or what the Zapatistas might call “leading by obeying”. Others seemed to hang back because, well, maybe they were a little jealous. They'd worked for decades for very little pay, just for this moment - and then it seemed, a movement popped off without them and they had nothing to do with it.

But that's not actually the case. The movement could not have emerged at that time and place, without the thousands of social justice warriors who set the stage before us – especially those who slogged through decades of neo-liberal proselytizing under Reagan, and then the full implementation of that agenda under Clinton and Bush. And the vast majority of folks involved in Occupy Wall Street well know it!

Damn, did we need their help. And I'll just go ahead and say it: As we field finger-waving from allies that didn't roll up their sleeves and join in when it counted the most, we can only assume that the snide commentary comes of a need to rationalize their failure to participate. Because the truth is, while we can understand why people may have found Occupy Wall Street unpalatable on multiple levels, a lot of those folks really should have played their part in helping to shape this moment, into a more effective and sustainable, radical and anti-oppressive movement.

So this is a call to you, our skilled forebears, to come on out in the event we get another chance like this again: And to sit back and listen with fresh ears to new ideas, innocent and naive and brave and innovative new ideas that you think you've heard before - to govern by obeying. And this is a call to the fresh generation of activists envigorated by Occupy Wall Street: We really need to listen to the people who've been doing this longer than we have, and learn how to make space for their contributions.

And if both of these things happen next time around, that moment of radicalism will almost certainly become a real movement.