The US constitution's Bill of Rights is envied by much of the English-speaking world, even by people otherwise not enthralled by The American Way Of Life. Its fundamental liberties – freedom of assembly, freedom of the press, freedom from warrantless search – are a mighty bulwark against overweening state power, to be sure.

But what are these rights actually worth in the United States these days?

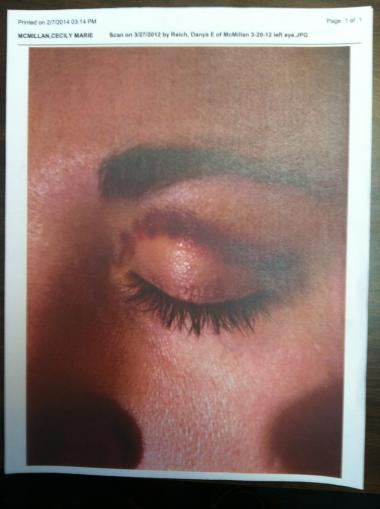

Ask Cecily McMillan, a 25-year-old student and activist who was arrested two years ago during an Occupy Wall Street demonstration in Manhattan. Seized by police, she was beaten black and blue on her ribs and arms until she went into a seizure. When she felt her right breast grabbed from behind, McMillan instinctively threw an elbow, catching a cop under the eye, and that is why she is being prosecuted for assaulting a police officer, a class D felony with a possible seven-year prison term. Her trial began this week.

McMillan is one of over 700 protestors arrested in the course of Occupy Wall Street's mass mobilization, which began with hopes of radical change and ended in an orgy of police misconduct. According to a scrupulously detailed report (pdf) issued by the NYU School of Law and Fordham Law School, the NYPD routinely wielded excessive force with batons, pepper spray, scooters and horses to crush the nascent movement. And then there were the arrests, often arbitrary, gratuitous and illegal, with most charges later dismissed. McMillan's is the last Occupy case to be tried, and how the court rules will provide a clear window into whether public assembly stays a basic right or becomes a criminal activity.

New York is not the only place where the first amendment's right to assembly continues to get gouged by police and prosecutors. In Chicago, police infiltrators goaded three activists into making Molotov cocktails; the young men were then charged with terror crimes – charges of which they were acquitted by an Illinois jury last week. Now that North Carolina has erupted into enormous protests against its far-right state government, we can likely expect police there to seek creative ways, legal and otherwise, to stifle mass political participation.

The freedom to assemble remains strong – as long as you're a single person holding up your sign on a highway embankment or some other lonely spot. But the right to engage in real public demonstrations has been effectively eviscerated by local ordinances and heavy-handed police tactics like aggressive surveillance, "kettling" protestors with movable plastic barriers, arbitrary closures of public spaces and the harassment and arrest of journalists who would tell the tale.

It's not exactly one of our sexier inalienable truths, the freedom to assemble. It was supposed to be a done deal, a ho-hum "first-generation right" clinched long ago in our society, threatened only in places like Ukraine or Thailand while Americans raced forward developing new "positive" rights like the right to water, or internet access. But like other "negative" freedoms against state interference – freedom of religion and freedom from warrantless and invasive searches – the right to assemble is being challenged at a time when thousands of Americans are taking to the streets.

As our rights melt away, we have taken some solace in the nasty responses to Pussy Riot's punk-rock protests in Putin's authoritarian state. At least we're not like Russia, where free speech is policed and controlled by law.

But what might happen to a homegrown Pussy Riot in New York? If, say, a politically conscious hip-hop group plugged in their amps near the altar of Saint Patrick's cathedral in midtown Manhattan, you can bet that misdemeanor trespassing would only be the beginning. Given that US police often have such an easy time padding their charges – remember Cecily McMillan – it's conceivable that an American Pussy Riot could face resisting arrest and assaulting an officer as well. That's two years in jail, which is the same as the sentence handed down to Pussy Riot's Maria Alyokhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova.

For decades, any hint of a comparison between freedom-loving America and authoritarian Russia has been viewed as the whiny hyperbole. But anecdotes and hypotheticals aside, how do Russia and the US compare when it comes to that fundamental index of negative liberty? Namely, how many people does the state lock up?

The US has the highest incarceration rate in the world. In 2012, the incarceration rate in the United States (707 per 100,000) was about one and a half times that of Russia (472) and over triple the peak rate of the old East Germany (about 200). The incarceration rate for black men in the US is over five times higher than that of the Soviet Union at the height of the gulag (pdf). These are of course different societies with different histories – but the brute fact of our hyperincarceration cannot be explained away.

Our clearly enumerated rights are supposed to guarantee our freedom, but in a landscape of extreme inequality – economic, racial and gender inequality – the letter of the law doesn't always amount to much. Changing this socioeconomic landscape requires mass mobilization – often raucous, often messy, and utterly vital to the health of any real democracy. With this channel of political activity overpoliced to the point of blockage, the result is a positive feedback loop of rising inequality and eroding freedoms.

Can this circuit be broken? The trial of Cecily McMillan could end in a lengthy prison term or it could end in probation. But such cases matter not just for the defendants, and not even just for our freedoms as ends in themselves. They matter for the future of the good life in the United States.