When Iya’Falola Omobola first crossed the Mississippi state border 10 years ago, she felt uneasy. A friend told her that she was “feeling the energy from all those bodies hanging in the trees.” Yet, Omobola’s feeling soon changed. Born into a family of civil rights and labor organizers in Cleveland, Ohio, Omobola came to see Jackson as the Phoenix that rises from the ashes. She came to feel increasingly connected to the city’s rich civil rights history: Jackson was the place where NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers was murdered in 1963; where the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee did much of its organizing for Mississippi’s Freedom Summer; and where Stokely Carmichael delivered an important speech in 1966 about black power as a psychological response to fear. Now, 50 years later, Omobola’s has become one of the many residents who has helped launch Jackson to the forefront of today’s civil and economic rights movement.

Last year, the city elected the now late Mayor Chokwe Lumumba, a former leader of the radical Republic of New Afrika group and a human rights lawyer. His successful campaign, largely organized by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, signaled the city’s commitment to working for racial justice. Now, despite Lumumba’s sudden death in office in February, the city is continuing this momentum by envisioning — and organizing toward — a radical new economy centered on worker-owned cooperatives.

In many ways, Jackson, Miss., is the ideal place for an economic justice movement to begin because the problems are so dire. Not only does the city have a long legacy of racial violence and discrimination, but the area is also socially and economically depressed, ranking toward the bottom of national educational and health indicators.

“We are in a place that is at the bottom,” explained Tyson Jackson, a former student organizer with the United Auto Workers and the former campaign manager for Antar Lumumba, the late mayor’s son who ran unsuccessfully for his father’s seat in the recent special election this past April. “That’s where you start. You start where the sickness is.”

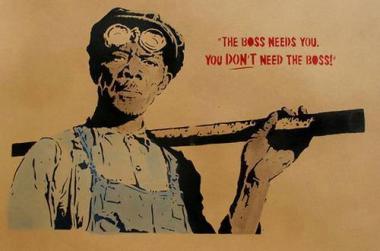

In this setting, worker-owned cooperatives seem to offer a potent combination. They appear to meet two needs at once — providing embattled low-income communities with the power to survive and to prosper economically, as well as the power for workers to govern themselves. “Cooperative development is a dangerous thing,” said Wendell Paris of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives at the Jackson Rising New Economies Conference, which was held the first weekend of May. “It teaches people to think independently. And it gives people the power of knowing how to stick together.”

Paris explains that cooperatives offer a way for Jackson residents — particularly African Americans — to access political power and exercise self-determination in the wake of the fierce counter-attacks to the gains of the 1960s and 1970s.

“The civil rights movement led to counter-movements to take the land away,” he explained. “[But] the independent cooperative movement was a way to hold onto land … Cooperatives are a way to bring change when all the forces are in place to stop you — forces of government, and the forces of financial power. There is no better organizing tool than cooperatives.”

A new way of doing business

While not all worker-owned cooperatives operate on the principle of one worker, one vote, these businesses differ dramatically from multinational corporations, economist Gar Alperovitz notes, because they don’t seek the highest possible profit at any cost. Instead, worker-owned cooperatives prioritize keeping operations local — and beneficial to the local community. Increased efficiency and morale are other commonly cited benefits of cooperatives, now seen as a key alternative to unchecked globalization.

Currently, Jackson has one fully established cooperative business: the Rainbow Coop in the Fondren neighborhood, one of the few areas where Jackson’s white and black communities merge.

“Every two weeks we decide how much to pay ourselves,” explained Luke Lundemo, one of the cooperative’s founding members. “We are guaranteed $10.50 an hour and 85 percent of the profits go to the employees. If we make a profit — and we usually do — we decide how much more pay we will get.” Lundemo and the cooperative’s co-founder Charlotte, both of whom are white, are now working closely with members of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement to develop new ideas for businesses and to help them take root among the city’s African American communities.

Participatory democracy meets electoral politics

Much of the momentum behind the cooperative movement in Jackson comes from last year’s historic election of the late mayor Chokwe Lumumba. Tyson Jackson explained that, before Lumumba’s election, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement organized monthly “People Assemblies,” which offered a significantly more collective and participatory vision for local government than Jackson residents had previously experienced. As the assemblies spread, Jackson explained, “[they] taught people that the government is not a separate entity outside of the community. They are the government themselves.”

For example, when a developer wanted to build mixed-income housing in Ward Two, a low-income area, Lumumba supported the plan. It would raise the city’s tax base without gentrifying, he argued. But the residents were against the plan out of a concern that their taxes would go up. True to the people, Lumumba dropped his support for the plan.

Tyson Jackson explained that, despite Lumumba’s passing, the recent Jackson Rising New Economies Conference was organized in the same inclusive way as the “People Assemblies.” He recalled all kinds of people coming to meetings. “One man, he had just gotten out of jail. He looked kind of menacing, with tattoos and everything,” Jackson remembered. “He said: ‘I just got out of jail. I’m here because I want to do something with my life.’ And this was in a board room in City Hall.”

International networks of cooperative economics

While the cooperative movement in Jackson seeks to address the city’s history of racial violence and economic injustice, the effort hasn’t only attracted the city’s African American residents. In fact, organizers and worker-owned cooperative members from across the world were drawn to the recent conference, where they brought their own histories of struggle to the movement. A former freedom fighter from Zimbabwe recounted his country’s extensive network of rural and urban cooperatives. He explained how, in the 1980s, the cooperative movement in Zimbabwe began with that new nation’s strongest sector — agriculture — before spreading to encompass transportation, manufacturing, urban housing and even pre-school education.

Meanwhile, Mazibuko Jara of South Africa, who was born in the poor labor-exporting Eastern Cape region, talked about how the country’s liberation movement morphed into a form of neoliberalism — an unexpected outcome. His comments seemed to moderate the generally optimistic tone of the conference by reminding the crowd of the fragility of even the hardest-fought movements for economic freedom.

“In South Africa, the black elite captured the movement,” he said. For Jara, the end of apartheid was not an unalloyed victory. “In 1994, black people voted as citizens,” he continued. “But those elections also freed white capital from its chains, allowing it to reach into the rest of the continent, and freeing up the establishment of a financial services industry.”

From self-knowledge to self-governance

Melvin “Ricky” Martin from the New Era Windows Company in Chicago also traveled to Jackson to share his experience helping form a cooperative. In 2008, he worked for a factory that employed 200 people. The owners abruptly announced that they were closing, citing cost reasons. He and other low-paid workers did not get paid for that month’s work, nor did they get compensation. Meanwhile, the owners rushed to re-open a new plant with cheaper workers. Martin was one of a small group of workers — some union members — who refused to leave. They occupied the factory for six days in what is being described as the first sit-down strike in America since the 1930s.

A few years later, Martin’s group bought the plant with a loan from The Working World, a group that helps train and finance cooperatives in Argentina, Nicaragua and in the United States. Martin and his co-workers resumed the production of windows and doors as a worker-owned cooperative.“The co-op was a way to give us back our lives,” he said. “This was not an opportunity that someone gave me, but one I made myself.”

In some ways, what Jackson’s seasoned organizers are attempting to do is achieve the transformation Martin experienced, but on a citywide level. As emcee Omobola explained, she sees Jackson as a place that is reawakening, as if from a stupor.

“This is a place that was very powerful. It went to sleep for a while,” she said, explaining that the city and its residents have now, finally, begun the process of awakening and relearning their identities. “I’m not saying this is only for African Americans. But I am an African American,” she said. “We have to understand who we are. Then we can be a model for the world.”

This piece was originally published on Waging Nonviolence.