On Christmas Day 2011, the hacktivist collective Anonymous ruined the day for a security firm that, throughout much of its history, enjoyed operating in the shadows.

The firm: Strategic Forecasting, Inc., an Austin, Texas-based intelligence-collecting contracting company better known as Stratfor. Its clients include some of the most profitable multinational corporations on the planet, such as the American Petroleum Institute, Archer Daniels Midland, Dow Chemical, Duke Energy, Northrop Grumman, Intel and Coca-Cola.

Anonymous hacked into the content management system of Stratfor’s computer system, eventually handing over 5.2 million emails and accompanying attachments to WikiLeaks, which coined the database the “Global Intelligence Files.”

Working through an informant named “Sabu,” who posed as a fellow “comrade,” federal officials tracked down the hacktivist responsible for the leak, Chicago’s Jeremy Hammond, just three months later.

In March 2012, the FBI raided Hammond’s apartment and handed him charges. After more than a year of sitting in the Manhattan Correctional Center, Hammond eventually settled out of court in May 2013. He pleaded guilty to violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, and his sentence will be handed down on Sept. 6. He may serve up to 10 years in prison.

Stratfor’s precursor, Pagan International, built the corporate public relations playbook still utilized by the firm today.

The goal of a corporate PR plan “must be to separate the fanatic activist leaders … from the overwhelming majority of their followers: decent, concerned people who are willing to judge us on the basis of our openness and usefulness,” Pagan stated in 1982, fully understanding that the public should never know this was the game plan.

Hammond — perhaps without knowing every detail of the history of the playbook itself – essentially cited it as the rationale behind his Stratfor hack and leak to WikiLeaks.

“I believe in the power of the truth. In keeping with that, I do not want to hide what I did or to shy away from my actions,” he stated in a press release announcing the plea deal. “I believe people have a right to know what governments and corporations are doing behind closed doors.”

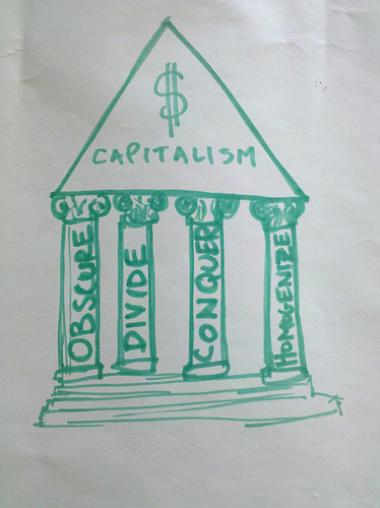

In this investigation, Mint Press examines Stratfor’s rise to power and its use of the “divide and conquer” philosophy to take on some of the largest boycott movements against multinational corporations.

‘Divide and conquer’

The story of Stratfor begins with a short-lived but deeply influential firm called Pagan International.

If there’s a short description of the modus operandi of Stratfor’s predecessors, military-like “divide and conquer” perceptions management — or rough-and-tumble public relations — is it.

That’s not by accident. Two of Pagan’s co-founders started their careers doing covert work for the U.S. military. Modern public relations got its start in military psychological operations, or psy-ops. “Divide and conquer” is one of the tenets laid out in the “U.S. Counterinsurgency Field Manual.”

Pagan International was named after Rafael D. Pagan Jr., who joined the U.S. Army in 1951 and spent two decades doing upper-level military intelligence work. He used it as a launching point into the corporate PR world.

“A former Army intelligence officer, the Potomac resident briefed Presidents Kennedy and Johnson on the Soviet bloc’s military and economic capabilities. He advised Presidents Nixon, Reagan and Bush on policies promoting Third World social and economic development,” explains his 1993 obituary in The Washington Times.

Upon leaving the Pentagon, Pagan got three public relations jobs for corporations seeking markets for their products in the developing world.

“Pagan began his international business career in 1970 as a senior executive in new business development with three major multinational companies, International Nickel of Canada (now Inco), Castle & Cooke (now Dole), and Nestle,” according to his obituary. “He specialized in addressing conflicts for multinational companies seeking to invest and operate in Third World countries.”

Pagan followed in the footsteps of the father of modern public relations, Edward Bernays, who helped with the PR surrounding United Fruit Company’s work with the U.S. government to foment a coup in 1954 in Honduras. Pagan also did PR for Castle & Cooke in Honduras.

Pagan’s experiences working in the Honduran “banana republic” under the U.S.-installed right-wing, corporate-friendly military dictatorship would suit him well for his the next step of his career: doing the PR bidding of multinational corporate behemoth Nestle.

The playbook in action for Nestle

Speaking at the April 1982 Public Affairs Council conference to his colleagues in the PR industry, Pagan revealed the skeleton of the playbook that would last all the way through the Stratfor days.

Pagan International arose out of the ashes of a controversial Nestle public relations campaign named, in Orwellian fashion, the “Nestle Coordination Center for Nutrition.” It was co-run by Pagan and Jack Mongoven.

Mongoven was once a reporter for The Chicago Tribune and served as an executive editor of Pioneer Newspapers before becoming a spokesman for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and then the Republican National Committee.

Nestle’s Coordination Center for Nutrition began in 1980 as a major public relations effort designed to fend off complaints and an eventual international boycott. Criticism of Nestle was spearheaded by the British group War on Want, which tracked the company’s marketing of powdered baby milk in the developing world in a 1974 investigation called “The Baby Killer.”

Nestle had decided the developing world would be a good place to sell its baby formula, despite the fact that the formula interrupted women’s lactation process and prevented their breasts from producing enough milk.

“Women who were induced to use [the] formula in place of breast milk often had no choice but to dilute the formula with contaminated water, leading to diarrhea, dehydration and death among … infants,” explain John Stauber and Sheldon Rampton in their book, “Toxic Sludge Is Good for You! Lies, Damn Lies and the Public Relations Industry.”

This behavior by Nestle created a global uproar and eventually planted the seeds of a boycott by more than 700 churches and activist groups.

Mongoven and Pagan — under the auspices of the Coordination Center for Nutrition, which shared office space with The Tobacco Institute, according to Legacy Tobacco Archive Library documents — decided the best response to the burgeoning social movement was to divide and conquer it.

One of their first strategies was to peel off some of strongest supporters of the anti-Nestle campaign — educators.

“Some of the boycott’s strongest support came from teachers, represented by the National Teachers Association, so NCCN courted support from American Federation of Teachers, a smaller, more conservative rival union,” wrote Stauber and Rampton.

Nestle also won over an ally from the inside of another institutional opponent: churches.

“To counter the churches involved in the boycott, they needed to find a strong church that would take their side,” Stauber and Rampton further explained. “The United Methodists were supporting the boycott, but through negotiations and piecemeal concessions, Nestle gradually succeeded in winning them over.”

To make amends, Nestle worked with the Infant Formula Audit Commission to ensure its global marketing practices were in line with World Health Organization rules. It was chaired by Edmund Muskie, a former U.S. senator and U.S. secretary of state under President Jimmy Carter.

The problem: Nestle created the commission, funded it and called all the shots. Few equipped with this knowledge were surprised when the commission concluded “the company has not been improperly ‘dumping’ baby formula on Third World hospitals,” as explained in The Los Angeles Times.

Muskie’s audit commission — or, better put, Nestle’s — is now seen as a “model” for corporations seeking to defuse sticky communication crises, as documented in a 1986 article in the Journal for Business Strategy.

For his successful efforts running what he would later describe as “a responsive, accurate corporate issue and trends warning system [with] analysis capability,” Pagan received the Public Relations Society of America’s prestigious Silver Anvil Award. Other industries have followed similar strategies, such as the shale gas industry’s “Energy in Depth” and corporate education reform’s “Stand for Children.”

Pagan International is born

Hot off a major victory over advocacy groups nationwide and having learned much from the “war,” Pagan and Mongoven hopped off the Nestle gravy train and started their own firm in 1985: Pagan International.

“The strong influence public and social issues today have on commercial operations has created a need for companies to evaluate carefully national and international policies affecting business,” Pagan said in a 1985 press release announcing the firm’s launch.

That press release further boasted of “an international business socio-political database” it had developed during the time of the Nestle battle royale, referring to its short-lived International Barometer database and newsletter and foreshadowing the database and newsletter Stratfor would market just over a decade later.

“Pagan said that this system enables [the firm] to advise clients on national and international trends and movements that can adversely affect corporations,” the press release further explains. “This gives the companies an opportunity to enter into public discussions and help define the parameters of the debate early on, rather than just react to agendas thrust upon them by activists and other groups.”

Enjoying a client list during its brief lifetime that included Dow Chemical, Novartis, Chevron and the government of Puerto Rico, Pagan International was hired by Royal Dutch Shell to fend off another international boycott for the company’s work with the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Activists demanded Shell stop doing business with South Africa until it was no longer an apartheid state, threatening a boycott if it failed to comply. Shell chose to continue “business as usual.”

The resulting boycott served as a business opportunity for Pagan International, which stepped in and — as it did with Nestle — sought to divide and conquer the boycott movement. Shell hired Pagan and Mongoven to do so under a now-notorious 268-page document called the “Neptune Strategy.”

“Neptune Strategy” was leaked to the press in 1987, greatly embarrassing both Shell and Pagan International.

Paralleling the Muskie audit commission, Pagan’s “Neptune Strategy” created an industry front group called the Coalition on Southern Africa — which shared office space and a phone line with Pagan — to divide boycott supporters into an overarching movement settling for weaker demands.

“Pagan … proposed that Shell ‘develop a task force’ of South Africans, church leaders, U.S. activists and executives that could issue a statement about the company’s role in helping South Africa’s blacks prepare for life after apartheid,” according to a 1987 piece appearing in Inter-Press Service. “And Pagan singled out key black activists and church leaders to help it carry out its plan.”

In the “Neptune Strategy,” Pagan outlined a strategy that fit the familiar pattern: isolate and then conquer the “fanatic activist leaders.”

“[P]ost-apartheid planning should deflect anti-apartheid groups attention away from the boycott and divestment efforts and direct their vision and efforts into productive channels,” explained the “Neptune Strategy.”

“Productive,” according to Pagan, is anything that would ensure Shell continues to produce high profit margins. After taking a beating by churches during the Nestle boycott, Pagan realized its bottom line hinged upon churches supporting Shell as it conducted business with apartheid South Africa.

“[M]obilized members of the religious communions provide a ‘critical mass’ of public opinion and economic leverage that should not be taken lightly,” Pagan wrote in the “Neptune Strategy.” “If they join the boycott and pressure for divestment, it will become a radically different and far more costly problem than it now is.”

Pagan International’s reputation soured after “Project Neptune” was revealed to the public and the firm lost the $800,000 of income it was receiving through its contract with Shell. Pagan also lost other key clientele after “Neptune” was exposed.

In 1990, Pagan shut its doors for good and filed for bankruptcy, opening the doors for ascendancy of the firm that would later merge into Stratfor: Mongoven, Biscoe & Duchin.

Rafael Pagan — who died in 1993 — was not invited to be a part of his former associate’s new firm, Mongoven, Biscoe & Duchin. His tactic of conquering and dividing activist movements and isolating the “fanatic activist leaders” lived on, though, through his former business partner, Jack Mongoven.

Mongoven teamed up with Alvin Biscoe and Ronald Duchin to create MBD in 1988. While “Biscoe appears to have been a largely silent partner at MBD,” according to the Center for Media and Democracy, Mongoven and Duchin played public-facing starring roles for the firm.

Duchin, like Pagan, had a military background. A graduate of the U.S. Army War College and “one of the original members of [Army] DELTA” — part of the broader Joint Special Operations Command that killed Osama Bin Laden — Duchin had jobs as a special assistant to the secretary of defense and as spokesman for Veterans for Foreign Wars prior to coming to Pagan.

Duchin served as head of the Pentagon’s news division during “Operation Eagle Claw,” President Jimmy Carter’s failed 1980 mission to use special forces to capture the hostages held in Iran.

Referred to by The Atlantic as the “Desert One Debacle” in a story Duchin served as a key confidential source for — as revealed in an email in the “Global Intelligence Files” announcing Duchin’s 2010 death — “Eagle Claw” ended with eight U.S. troops dying, four wounded, one helicopter destroyed, and President Carter’s reputation in the tank. The failed and lethal mission served as the impetus for the creation of the U.S. Special Operations.

Largely avoiding the limelight while working as Pagan’s vice president for Issue management and strategy — the brains of the operation — Duchin became a notorious figure among dedicated critical observers of the public relations industry while co-heading MBD. During MBD’s 15 years of existence, its clients included Big Tobacco, the chemical industry, Big Agriculture and probably many other industries never identified due to MBD’s secretive nature.

MBD worked on behalf of Big Tobacco to fend off any and all regulatory efforts aimed in its direction. Philip Morris paid Jack Mongoven $85,000 for his intelligence-gathering prowess in 1993.

“Get Government Off Our Back,” an RJ Reynolds front group created in 1994 by MBD for the price of $14,000 per month, serves as a case in point of the type of work MBD was hired to do by Big Tobacco.

“The firm has developed initiatives for RJ Reynolds that advocate pro-tobacco goals through outside organizations; among other projects, the firm organized veterans organizations to oppose the workplace smoking regulation proposed by OSHA,” explains a 2007 study appearing in the American Journal of Public Health. “[It] was created to combat increasing numbers of proposed federal and state regulations on the use and sale of tobacco products.”

Paralleling the Koch Family Foundations-funded Americans for Prosperity groups of today, “Get Government Off Our Back” held rallies nationwide in March 1995 as part of “Regulatory Revolt Month.”

“Get Government Off Our Back” dovetailed perfectly with the Republican Party’s 1994 “Contract with America” that froze new federal regulations. The text of the “Contract” matched “Get Government Off Our Back” “nearly verbatim,” according to the American Journal of Public Health study.

‘Radicals, Idealists, Realists, Opportunists’

While its client work was noteworthy, the formula Duchin created to divide and conquer activist movements — a regurgitation of what he learned while working under the mentorship of Rafael Pagan — has stood the test of time. It is still employed to this day by Stratfor.

Duchin replaced Pagan’s “fanatic activist leaders” with “radicals” and created a three-step formula to divide and conquer activists by breaking them up into four subtypes, as described in a 1991 speech delivered to the National Cattleman’s Association titled, “Take an Activist Apart and What Do You Have? And How Do You Deal with Him/Her?”

The subtypes: “radicals, idealists, realists and opportunists.”

Radical activists “want to change the system; have underlying socio/political motives’ and see multinational corporations as ‘inherently evil,’” explained Duchin. “These organizations do not trust the … federal, state and local governments to protect them and to safeguard the environment. They believe, rather, that individuals and local groups should have direct power over industry … I would categorize their principal aims … as social justice and political empowerment.”

The “idealist” is easier to deal with, according to Duchin’s analysis.

“Idealists…want a perfect world…Because of their intrinsic altruism, however, … [they] have a vulnerable point,” he told the audience. “If they can be shown that their position is in opposition to an industry … and cannot be ethically justified, they [will] change their position.”

The two easiest subtypes to join the corporate side of the fight are the “realists” and the “opportunists.” By definition, an “opportunist” takes the opportunity to side with the powerful for career gain, Duchin explained, and has skin in the game for “visibility, power [and] followers.”

The realist, by contrast, is more complex but the most important piece of the puzzle, says Duchin.

“[Realists are able to] live with trade-offs; willing to work within the system; not interested in radical change; pragmatic. The realists should always receive the highest priority in any strategy dealing with a public policy issue.”

Duchin outlined a corresponding three-step strategy to “deal with” these four activist subtypes.

First, isolate the radicals. Second, “cultivate” the idealists and “educate” them into becoming realists. And finally, co-opt the realists into agreeing with industry.

“If your industry can successfully bring about these relationships, the credibility of the radicals will be lost and opportunists can be counted on to share in the final policy solution,” Duchin outlined in closing his speech.

Bringing the ‘Duchin Formula’ to Stratfor

Alvin Biscoe passed away in 1998 and Jack Mongoven passed away in 2000. Just a few years later, MBD — now only Ronald Duchin and Jack’s son, Bartholomew or “Bart” — merged with Stratfor in 2003.

A book by John Stauber and Sheldon Rampton — “Trust Us, We’re Experts!” — explains that MBD promotional literature boasted that the firm kept “extensive files [on] forces for change [which] can often include activist and public interest groups, churches, unions and/or academia.”

“A typical dossier includes an organization’s historical background, biographical information on key personnel, funding sources, organizational structure and affiliations, and a ‘characterization’ of the organization aimed at identifying potential ways to co-opt or marginalize the organization’s impact on public policy debates,” the authors proceeded to explain.

MBD’s “extensive files” on “forces for change” soon would morph into Stratfor’s “Global Intelligence Files” after the merger.

What’s clear in sifting through the “Global Intelligence Files” documents, which were obtained by WikiLeaks as a result of Jeremy Hammond’s December 2011 hack of Stratfor, is that it was a marriage made in heaven for MBD and Stratfor.

The “Duchin formula” has become a Stratfor mainstay, carried on by Bart Mongoven. Duchin passed away in 2010.

In a December 2010 PowerPoint presentation to the oil company Suncor on how best to “deal with” anti-Alberta tar sands activists, Bart Mongoven explains how to do so explicitly utilizing the “radicals, idealists, realists and opportunists” framework. In that presentation, he places the various environmental groups fighting against the tar sands in each category and concludes the presentation by explaining how Suncor can win the war against them.

Bart Mongoven described the American Petroleum Institute as his “biggest client” in a January 2010 email exchange, lending explanation to his interest in environmental and energy issues.

Mongoven also appears to have realized something was off about Chesapeake Energy’s financial support for the Sierra Club, judging by November 2009 email exchanges. It took “idealists” in the environmental movement a full 2 ½ years to realize the same thing, after Time magazine wrote a major investigation revealing the fiduciary relationship between one of the biggest shale gas “fracking” companies in the U.S. and one of the country’s biggest environmental groups.

“The clearest evidence of a financial relationship is the note in the Sierra Club 2008 annual report that American Clean Skies Foundation was a financial supporter that year,” wrote Mongoven in an email to the National Manufacturing Association’s vice president of communications, Luke Popovich. “According to McClendon, American Clean Skies Foundation was created by Chesapeake and others in 2007.”

Bart Mongoven also used the “realist/idealist” paradigm to discuss climate change legislation’s chances for passage in a 2007 article on Stratfor’s website.

“Realists who support a strong federal regime are drawn to the idea that with most in industry calling for action on climate change, there is no time like the present,” Mongoven wrote. “Idealists, on the other hand, argue that with momentum on their side, there is little that industry could do in the face of a Democratic president and Congress, and therefore time is on the environmentalists’ side. The idealists argue that they have not gone this far only to pass a half-measure, particularly one that does not contain a hard carbon cap.”

And how best to deal with “radicals” like Julian Assange, founder and executive director of WikiLeaks, and whistleblower Bradley Manning, who gave WikiLeaks the U.S. State Department diplomatic cables, the Iraq and Afghanistan war logs and the “Collateral Murder” video? Bart Mongoven has a simple solution to “isolate” them, as suggested by Duchin’s formula.

“I’m in favor of using whatever trumped up charge is available to get [Assange] and his servers off the streets. And I’d feed that shit head soldier [Bradley Manning] to the first pack of wild dogs I could find,” Mongoven wrote in one email exchange revealed by the “Global Intelligence Files.” “Or perhaps just do to him whatever the Iranians are doing to our sources there.”

Indeed, the use of “trumped up charges” is often a way the U.S. government deals with radical activists, as demonstrated clearly during the days of the FBI’s Counter-Intelligence Program during the 1960s, as well as in modern-day Occupy movement-related cases in Cleveland and Chicago.

‘Information economy’s equivalent of guns’

Just days after the Sept. 11, 2011, attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon, The Austin Chronicle published an article on Stratfor that posed the rhetorical question as its title, “Is Knowledge Power?”

The answer, simply put: yes.

“What Stratfor produces is the information economy’s equivalent of guns: knowledge about the world that can change the world, quickly and irrevocably,” wrote Michael Erard for The Chronicle. “So if Stratfor succeeds, it’s because more individuals and corporations want access to information that helps them dissect an unstable world — and are willing to pay steady bucks for it.”

When it comes down to it, Stauber concurs with the “guns” metaphor and Duchin’s “war” metaphors.

“Corporations wage war upon activists to ensure that corporate activities, power, profits and control are not diminished or significantly reformed,” said Stauber. “The burden is on the activists to make fundamental social change in a political environment where the corporate interests dominate both politically and through the corporate media.”

Stauber also believes activists have a steep learning curve and are currently being left in the dust by Pagan, MBD, Stratfor and others.

“The Pagan/MBD/Stratfor operatives are much more sophisticated about social change than the activists they oppose, they have limitless resources at their disposal, and their goal is relatively simple: make sure that ultimately the activists fail to win fundamental reforms,” he said. “Duchin and Mongoven were ruthless, and I think they were often amused by the naivete, egotism, antics and failures of activists they routinely fooled and defeated. Ultimately, this is war, and the best warriors will win.”

One thing’s for certain: Duchin’s legacy lives on through his “formula.”

“The 4-step formula is brilliant and has certainly proven itself effective in preventing the democratic reforms we need,” Stauber remarked, bringing us back to where we started in 1982 with Rafael Pagan’s remarks about isolating the “fanatic activist leaders.”

This piece was originally published in Mint Press News.