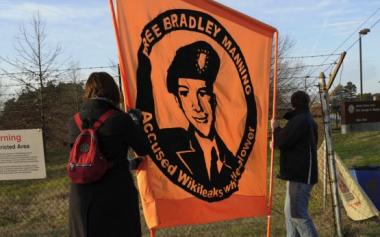

Below is a recap of the government’s evidence that Bradley Manning “aided the enemy.” Today, the defense begins its merits case.

On February 28, 2013, Pfc. Bradley Manning pled guilty to ten lesser offenses that could have put him in jail for up to 20 years, taking responsibility for releasing classified documents to WikiLeaks as an act of conscience. But that wasn’t enough for prosecutors, who decided to move forward on all counts, seeking to imprison Manning for the rest of his life, without a chance for parole. The government said it could prove Manning knew that by dealing with WikiLeaks he was dealing al Qaeda. But now that the government has rested its case, many have been shocked to see that prosecutors’ evidence is weak, ambiguous, and circumstantial. It appears that the government is more interested in trying to connect tangential dots, in order to smear a heroic whistleblower as a traitor, than seeking any type of justice.

Aiding the enemy (UCMJ Article 104)

The government must prove “actual knowledge by PFC Manning that by giving the intelligence to WikiLeaks, that he was actually giving intelligence to the enemy through this indirect means. The Court has held that PFC Manning cannot violate Article 104 by committing an act inadvertently, accidentally, or negligently that has the effect of aiding the enemy.”

To prove Manning’s knowledge at the time of the disclosure, the government has called witnesses who reviewed his computers to testify that he searched the military’s Google for “WikiLeaks,” and that he chatted with ‘press association,’ an account that prosecutors say is associated with Julian Assange.

Circumstantial tweets, documents

Prosecutors have entered a few items of evidence as well: two WikiLeaks tweets, a 2009 ‘Most Wanted Leak’ list, and an Army Counterintelligence Center (ACIC) report on WikiLeaks.

One of the tweets announces possession of an encrypted video, and requests “super computer time” to decrypt it. Prosecutors imply this is evidence that Manning gave WikiLeaks the never-released Garani airstrike video. This video was taken from U.S Central Command’s (CENTCOM) servers. But the only copy of CENTCOM’s video seen elsewhere is on the computer of Jason Katz, not Bradley Manning. Katz was fired from the Department of Energy for “inappropriate computer activity,” and had decryption software on his computer. Forensic examiners found no connection whatsoever between Katz and Manning, or that they ever even knew one another. WikiLeaks never released a Garani video.

Prosecutors say that Manning transmitted that video and accompanying documents in both November 2009 and April 2010. Manning’s defense said that there was only the latter transmission, and when the government insisted on charging the earlier one in an effort to show a months-long string of leaks, Manning pled not guilty as charged. Then in court, forensic examiners said there was only evidence of an April 2010 transmission, nothing from 2009. See Alexa O’Brien’s more detailed account of how the government’s airstrike video case fell apart.

The other tweet requests “as many .mil email addresses as possible,” meaning all military addresses. The government connects this with Manning’s downloading of the Global Address List in Iraq, comprising contact information for U.S. Forces in Iraq, which no one contends Manning transmitted.

Finally, the government entered as evidence a draft document on WikiLeaks’ website in 2009 (which forensic examiners say can’t be located on the site today), titled ‘Most Wanted Leaks.’ The list compiles desired documents – but a defense-submitted version of the document says it compiles “concealed documents or recordings most sought after by a country’s journalists, activists, historians, lawyers, police, or human rights investigators.”

If Manning had viewed all three of these items, they could be considered circumstantial evidence that he could be working under WikiLeaks’ direction. But the government has no evidence that Manning ever saw any of them. More to the point, none suggest any connection or association between WikiLeaks and al Qaeda – nothing to suggest that giving documents to WikiLeaks meant giving indirectly to AQ or any of its affiliates.

Ambiguous U.S. Army report

The only evidentiary item tied to Manning’s knowledge and which mentions terrorist organizations is a U.S. ACIC report, titled ‘Wikileaks.org—An Online Reference to Foreign Intelligence Services, Insurgents, or Terrorist Groups?’

But as the defense established in cross-examination, as the interrogative title implies, and as Marcy Wheeler notes, the document isn’t definitive about whether these groups visited WikiLeaks.

“[N]ot only doesn’t this report assert that leaking to WikiLeaks amounts to leaking to our adversaries; on the contrary, the report identifies that possibility as a data gap,” Wheeler writes. “But it also provides several pieces of support for the necessity of something like WikiLeaks to report government wrongdoing.”

When defense lawyer David Coombs asked Captain Casey Fulton, who deployed to Baghdad with Manning and who headed his intelligence section, about any specific websites that America’s enemies were known to visit, she could only cite social networking websites where people post personal information, like Facebook, and Google Maps.

Manning’s instructor from intelligence analyst training, Troy Moul, admitted in court, “I had never even heard of the term WikiLeaks until I was informed [Bradley] had been arrested.”

Enemies’ “receipt” of WikiLeaks-released documents

In April 2013, Judge Denise Lind ruled that the government has to prove that America’s adversaries received intelligence information released by Bradley Manning. The defense had actually moved to strike that requirement, knowing prosecutors intended to bring provocative and misleading evidence that Osama bin Laden had WikiLeaks-released documents on his computer.

To prove receipt, the government submitted a stipulation of fact, declaring that on the raid of Osama bin Laden’s Abbottobad compound on May 2, 2011, U.S. agents found digital media containing a letter from bin Laden. He’d asked another al Qaeda member for U.S. defense information, and the member responded with WikiLeaks-released documents.

It also submitted a stipulation regarding Adam Gadahn, an American who joined al Qaeda as a recruiter, and a video, released on June 3, 2011, in which Gadahn cites WikiLeaks documents. Gadahn plays ‘Collateral Murder,’ and says that America’s “interests are today spread all over the place and easily accessibly as the leak of America’s State Department cable on critical foreign dependency makes so clear.”

What’s so striking and rarely mentioned about either of these items is their dates. The bin Laden evidence was discovered in May 2011, and the video was discovered a month later – both several months after the government charged Bradley Manning with “aiding the enemy,” which was on March 1, 2011. If the government contends that “receipt” is required to prove aiding the enemy, and it didn’t have proof of receipt until May 2011, why did it charge Manning with Article 104 in March?

What else does Al Qaeda find ‘useful’?

Their final piece of “aiding the enemy” evidence did come before that charge, but it’s also incredibly flimsy. Part 6 of the Gadahn stipulation cites the Winter 2010 issue of Inspire Magazine, published online in January 2011. That issue, on page 44-45, says that “’[a]nything useful from WikiLeaks’ is useful for archiving.”

Do we really want to criminalize all of the publicly available information that al Qaeda and AQAP read and use? Doesn’t this prosecution make anything on the Internet a potential aid to the enemy?

In July 2010, Canada Free Press reported that Inspire’s first issue favorably references Noam Chomsky. In September 2011, AQ released a video in which bin Laden encouraged Americans to read Bob Woodward’s “Obama’s Wars.”

As Glenn Greenwald wrote earlier this year,

“If bin Laden’s interest in the WikiLeaks cables proves that Manning aided al-Qaida, why isn’t bin Laden’s enthusaism for Woodward’s book proof that Woodwood’s leakers – and Woodward himself – are guilty of the same capital offense? This question is even more compelling given that Woodward has repeatedly published some of the nation’s most sensitive secrets, including information designated “Top Secret” – unlike WikiLeaks and Manning, which never did.”

As Michael Isikoff reported in 2010, Woodward’s book disclosed “the code names of previously unknown National Security Agency programs, the existence of a clandestine paramilitary army run by the CIA in Afghanistan, and details of a secret Chinese cyberpenetration of Obama and John McCain campaign computers.”

This is certainly information that al Qaeda is interested in and which Woodward and his sources caused to be published. But does that mean Woodward “aided the enemy”? Certainly not.

Prosecutors would extend their argument at least that far. In January 2013, they claimed that they would charge Manning the same way if he had leaked to the New York Times instead of WikiLeaks. Times journalists denounced the claim and the charge more broadly, calling it “excessive.”

“Excessive” is an understatement. If Judge Lind affirms the government’s dangerous theory on exceptionally thin evidence, whistleblowing as we know it will essentially be considered treasonous.

In response to Bradley Manning’s disclosures, the government – which already over-classifies exponentially – cracked down on leaks and information security, instead of the crimes he exposed. Shining public light on secret crimes is only becoming harder and harder. It’s no wonder NSA whistleblower specifically cited Manning’s persecution in requesting asylum outside of the U.S.

Follow the case against Private Manning.

Share +

- Share Surprising Lack of Evidence Against Manning Confirms Over-Prosecution on Facebook

- Tweet Surprising Lack of Evidence Against Manning Confirms Over-Prosecution!

- Share Surprising Lack of Evidence Against Manning Confirms Over-Prosecution on Google +

- Reddit Surprising Lack of Evidence Against Manning Confirms Over-Prosecution!