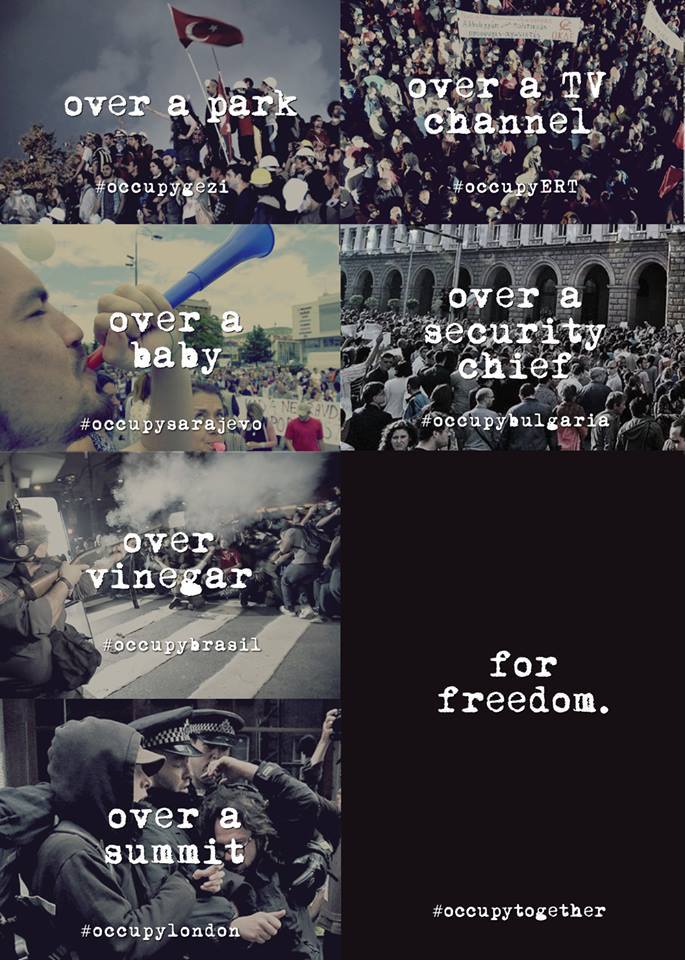

Once again, it’s kicking off everywhere: from Turkey to Bosnia, Bulgaria and Brazil, the endless struggle for real democracy resonates around the globe.

What do a park in Istanbul, a baby in Sarajevo, a security chief in Sofia, a TV station in Athens and bus tickets in Sao Paulo have in common? However random the sequence may seem at first, a common theme runs through and connects all of them. Each reveals, in its own particular way, the deepening crisis of representative democracy at the heart of the modern nation state. And each has, as a result, given rise to popular protests that have in turn sparked nationwide demonstrations, occupations and confrontations between the people and the state.

In Turkey, protesters have been taking to the streets and clashing with riot police for over two weeks in response to government attempts to tear down the trees and resurrect an old Ottoman-era barracks at the location of Istanbul’s beloved Gezi Park. But, as I indicated in a lengthy analysis of the protests, the violent police crackdown on #OccupyGezi was just the spark that lit the prairie, allowing a wide range of grievances to tumble in, ultimately exposing the crisis of representation at the heart of Erdogan’s authoritarian neoliberal government.

Now, protests over similar seemingly “trivial” local grievances are sparking mass demonstrations elsewhere. In Brazil, small-scale protests against a hike in transportation fees in Sao Paulo revealed the extreme brutality of the police force, which violently assaulted protesters — even pepper spraying a camera man, shooting a photographer in the eye with a rubber bullet, and arresting those carrying vinegar to protect themselves from the tear gas. After four nights of violent repression this week, the protests now appear to be gaining momentum.

Fed up with increasing inflation, crumbling infrastructure and stubbornly high inequality and crime rates, many Brazilians are simply outraged that the government is willing to invest billions into pharaonic projects that do not only ignore the people’s plight but actively undermine it. The militarization and bulldozing of the poor favelas and indigenous villages ahead of the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics are a case in point. As usual, the ruling Workers’ Party seems more concerned about pleasing capital than helping workers.

Meanwhile, in Sarajevo, the inability of a family to obtain travel ID for their sick baby — who needs urgent medical attention that she cannot receive in Bosnia-Herzegovina — exposed the fundamental flaws at the heart of the nominally democratic post-Yugoslavian state. On June 5, while the government was busy negotiating with foreign bankers to attract new investment, thousands of people occupied parliament square, temporarily locking the nation’s politicians up inside and forcing the prime minister to escape through a window.

While competing ethnic fractions vie for political power, the Bosnian people continue to suffer. By playing the race and religion cards, Bosnian politicians hope to keep the people divided while retaining the financial spoils of foreign investment and World Bank and EU development loans for themselves. But in a sign that most ethnic divisions are politically rather than socially constructed, the Occupy Sarajevo protesters now have a simple message for their politicians: “you are all disgusting, no matter what ethnicity you belong to.”

On Friday, Bulgaria joined the budding wave of struggles that began in Tunisia and Egypt in 2011 and that was recently revived through the Turkish uprising. After the appointment of media (and mafia) mogul Delyan Peevski as head of the State Agency for National Security, tens of thousands took to the streets of Sofia and other cities throughout the country to protest his appointment, which was approved by parliament without any debate and with a mere 15 minutes between his nomination and his (pre-guaranteed) election.

Chanting “Mafia” and calling upon Peevski to resign, the Bulgarians are warning their politicians that a limit has been reached. Ever since the transition from state communism to democratic capitalism empowered a tiny minority of oligarchs to enrich themselves by feeding off the state’s public possessions, Bulgaria has been effectively ruled by a Mafia kleptocracy. As in any capitalist state, political and business elites have become one, undermining the promise of democracy the Bulgarians were made at the so-called End of History.

Greece, in the meantime, finally appears to have been waken up from its austerity-induced slumber. Following the decision of the Troika’s neoliberal handmaiden, Antonis Samaras, to shut down the state’s public broadcaster ERT overnight and to fire its 2,700 workers without any warning whatsoever, the workers of ERT simply occupied the TV and radio stations and continued to emit their programs through livestreaming, making ERT the first worker-run public broadercaster in Europe. ERT workers have since been joined by tens of thousands of protesters and workers, who on Thursday held a nationwide general strike to protest the ERT’s closure.

At first sight, it may seem like these protests are all simply responses to local grievances and should be read as such. But while each context has its own specificities that must be taken into account, it would be naive to discard the common themes uniting them. As my friend, colleague and fellow ROAR contributor Leonidas Oikonomakis just pointed out in a new opinion piece, the Turkish uprising may have started over a couple of trees, but we shouldn’t let that blind us to the forest: the obvious structural dimension at play in this new wave of struggles.

If we take a closer look at each of the protests, we find that they are not so local after all. In fact, each of them in one way or another deals with the increasing encroachment of financial interests and business power on traditional democratic processes, and the profound crisis of representation that this has wrought. Furthermore, the protests show a dawning awareness that the divide-and-rule practices of the ruling class everywhere — pitching the religious against the secular, Bosnians against Serbs, blacks against indigenous against whites, poor against slightly-less-poor, and ‘natives’ against immigrants — are just part of a strategy to keep us from realizing our own power.

In a word, what we are witnessing is what Leonidas Oikonomakis and I have called the resonance of resistance: social struggles in one place in the world transcending their local boundaries and inspiring protesters elsewhere to take matters into their own hands and defy their governments in order to bring about genuine freedom, social justice and real democracy. The resonance of these struggles across national, ethnic and religious boundaries tells us that three decades of neoliberal peace since the End of History were not really “peace” at all; they were merely the temporary victory of other side in a hidden global class war.

Now that has come to an end. A new Left has risen, inspired by a fresh autonomous spirit that has long since cleansed itself of the stale ideological legacies and collective self-delusions that animated the political conflicts of the Cold War and beyond. One chant of the protesters in Sao Paulo revealed it all: “Peace is over, Turkey is here!” And so are Bulgaria, Bosnia and Greece — as well as Tunisia, Egypt, Spain, Chile, Mexico, Québec and every other place in the world where the people have risen up in the global struggle for real democracy.

The ominous bottom-line for those in power is simple: we are everywhere. And this global occupation thing? It’s only just getting started.

Originally published on ROAR Magazine