In a small gallery space on Stanton Street on New York City’s Lower East Side, Molly Crabapple has visualized what resistance looks like. Her dramatic densely packed spaces of liberation open your eyes as you walk out of the space. It’s a potent and (accidentally nostalgic) reminder of what the 2011 moment meant. On this May Day, it’s good to remember that resistance isn’t about violence, it isn’t gendered masculine, and it’s not the preserve of white privilege. It is fun, it’s lovely, it’s life-enhancing, it reminds us what love means above and beyond heteronormative coupling clichés.

There were nine paintings in the show on themes ranging from debt to Syntagma Square. Above is Our Lady of Liberty Park. I’m going to talk art for a bit here, people–if that makes you allergic, skip a paragraph or two. The space is organized symbolically, not literally. It takes form around the iconic body of Our Lady, the icon of Occupy. The icon is gendered female and is visibly non-white. She is not “real” but the assembled collective projection of the occupiers. In her hair is “The Red Thing,” the statue from the park. Her dress becomes a sheltering tent. She is us.

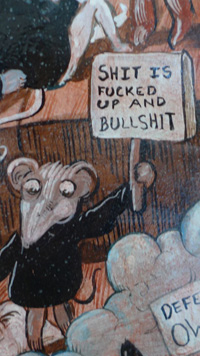

The icon is in the syncretic tradition of the Americas, whereby the enslaved or colonized indigenous peoples projected their religious and cultural traditions into the visual vocabulary of colonizing Christianity. That is to say, they dressed up their own ideas in Christian disguise. In this way, the resistant message was effectively concealed by virtue of being not fully visible. Crabapple isn’t disguising. Here, for example, the iconic sign of OWS:

But rather than put it in the hands of a protestor, who would then have to be marked (gender/ethnicity/age/body type), she transforms the movement into the visual vocabulary of comics. Crabapple is close here to the work of graphic artist Art Spiegelman, who represents people as mice in Maus and In the Shadow of No Towers. As Spiegelman does, Crabapple represents the forces of oppression as domestic animals, in her case dogs:

The scene above is a recognizable reworking of the pepper-spraying of young women by Deputy Inspector Anthony Bologna on September 26, 2011. It’s also now an iconic rendering of what have become known as iconic photographs. The point here would be that those who don’t know or remember the context of the occupation can still see what’s happening and realize it to be oppressive. Many of the photographs and videos from the day itself were unclear and had to be slowed down or captioned.

The other paintings in the series of nine make it clear that we should not take the painted scenes literally. Look for a moment at Dégage, Crabapple’s icon of the Tunisian revolution:

Dégage, the icon of revolution, is visibly non-human, a divinity. Her stylized gestures recall the Hindu goddess Kali, the goddess of destruction. Her wildly flowing hair evokes the figure of the Medusa, whose very glance turns people to stone. For Freud, you will recall, the Medusa is the symbol of castration, the cancellation of the male gaze. Dégage is not simply a woman–her face is a mask, her body is made of fire. It is the “fire next time” promised by James Baldwin, not a fire that consumes or endangers. Like the Burning Bush, the revolution is on fire but does not go out. Its practitioners here are birds, flying freely away from the cops, who uselessly swipe with their batons. Everywhere is the slogan: Dégage–stand down–que se vayan todos.

It’s really only up close that you get a sense of the energy and life in the series. The paintings know that the revolution and the occupation were not singular but plural; not nouns but verbs. It was what we did, what was done:

The birds flock around the dog-cops, landing on their batons, carrying off their shields and taunting them with the banner Dégage. Where Alfred Hitchcock used birds as the symbol for his characteristic loathing of female sexuality, women and the feminine in his 1963 classic The Birds. Almost all common US songbirds are in decline, some to the brink of being endangered species. Here the birds have escaped from the cage at the heart of the fire. They slip off their Guy Fawkes/Anonymous masks to claim freedom. Right now on the walls of Cairo is a graffito: “O stupid regime, hear my demand: freedom, freedom.”

When you spend time with these paintings, you hear this demand and you see the resistance.

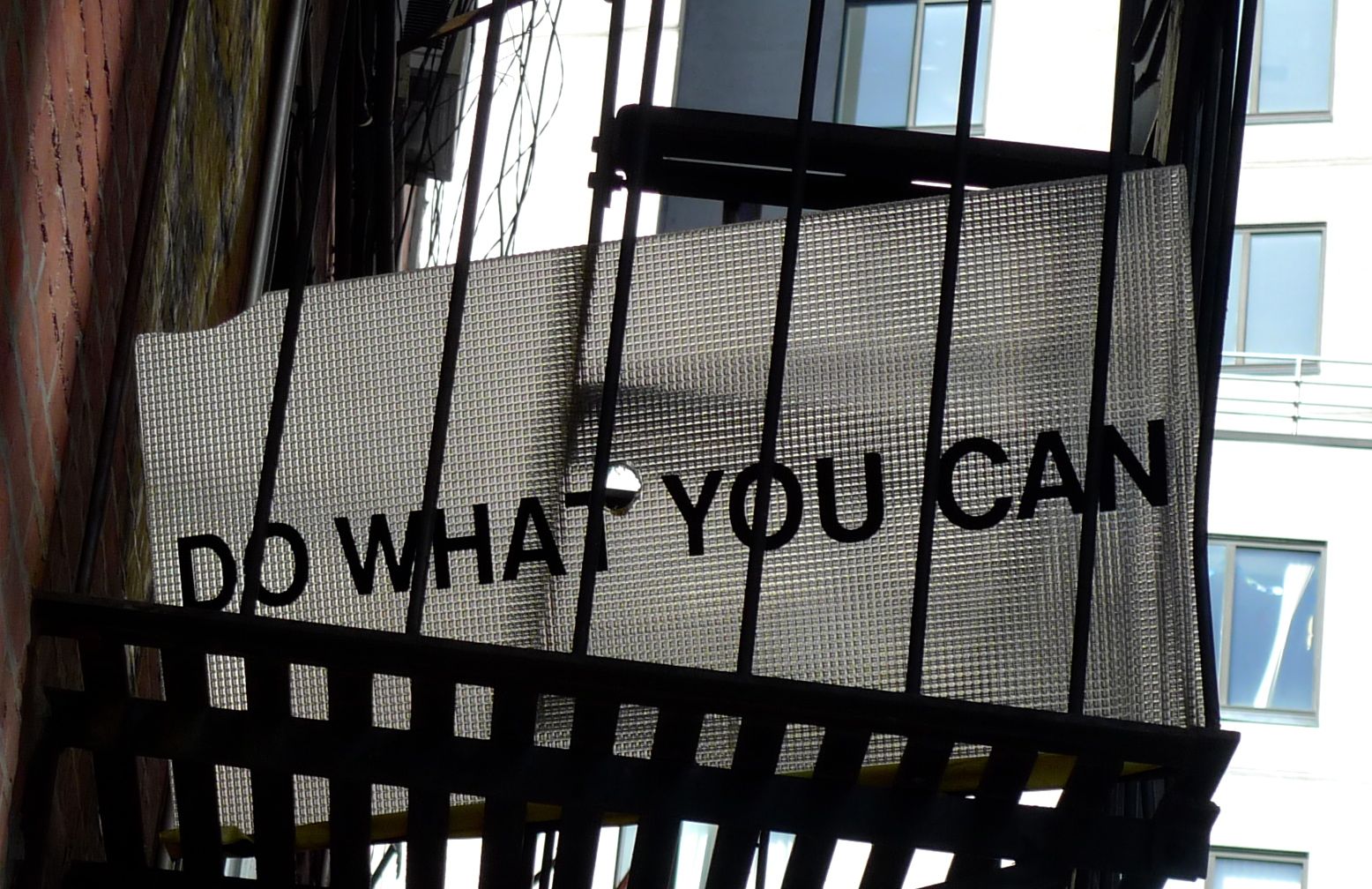

On my way home, I saw these things. Above Paper Tiger TV, the radical broadcasters who housed Global Revolution the live-streamers of OWS, a protest against drones

On a fire-escape on East 1st Street, whether as an art work, a sign, or a discarded sky light:

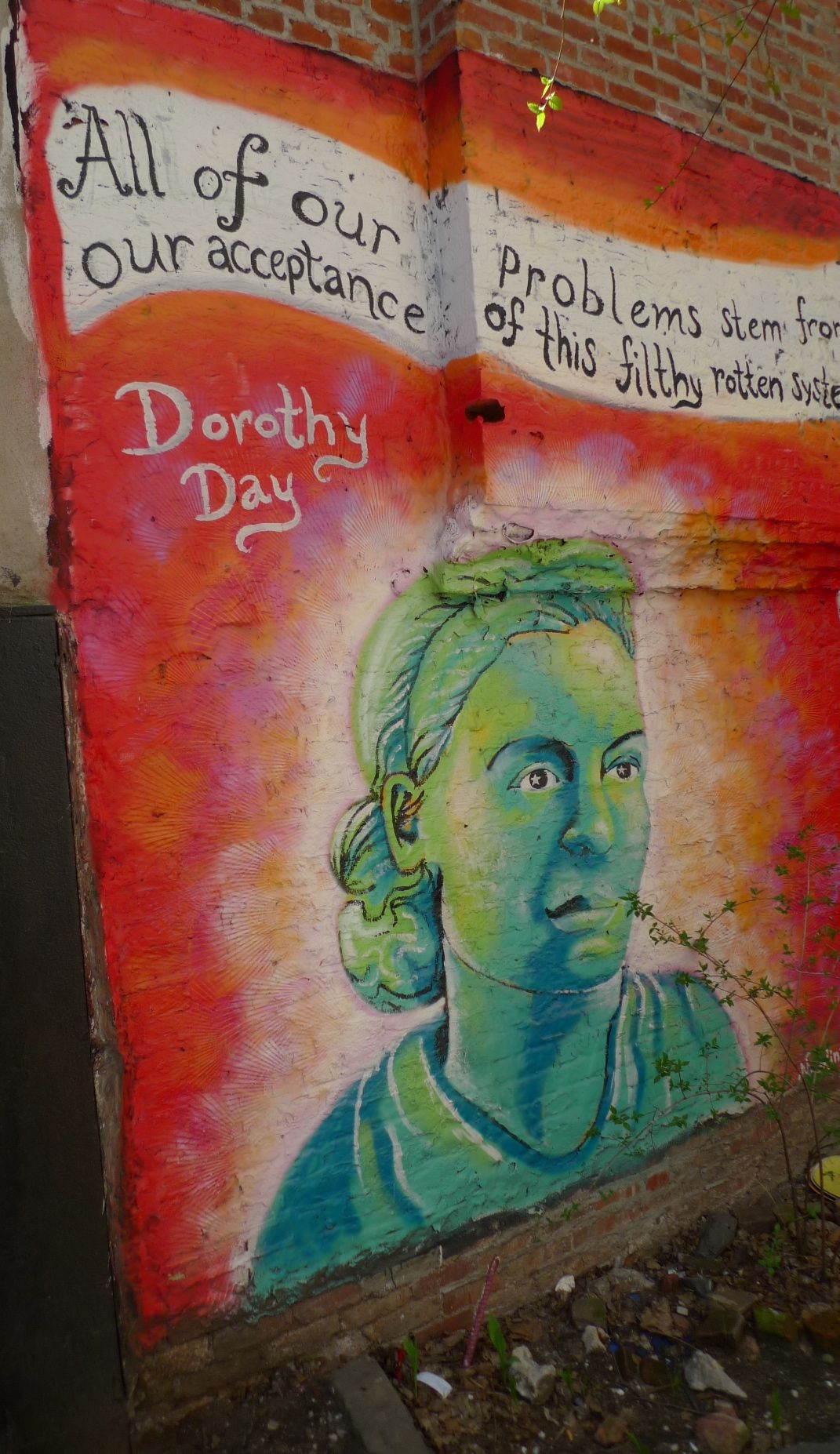

The Dorothy Day garden with its radical murals on East 1st:

“All of our problems stem from/Our acceptance of this filthy rotten system.” Plus one to that.

And I saw that the Yippie Café, site of endless OWS and other radical meetings, has a new sign:

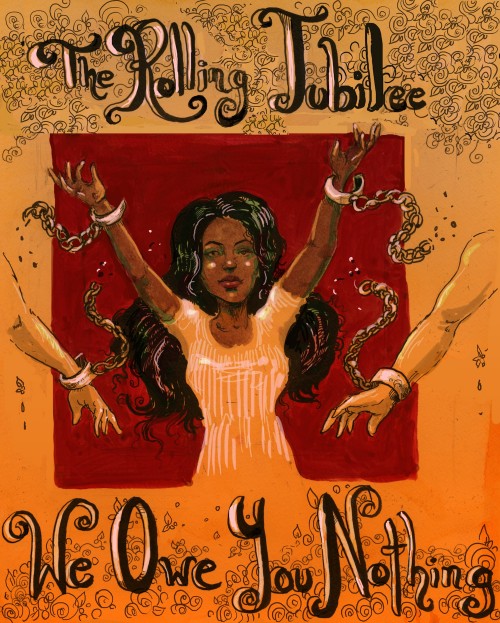

A final word: some Internet chatter wonders if Molly Crabapple had anything to do with Occupy anyway–she did, she was there, I saw her many times and she did a great poster for May Day last year and another one for Strike Debt’s Rolling Jubilee (below)

In case you’re wondering–no we didn’t use it and, yes, we were idiots not to do so.

And even sillier chatter about the cost of the paintings. Yes, they are $10,000 each. Some guy is selling paintings of WalMart for $40,000 apiece. Remember an artist gives up 50% to the gallery. So if she sells out the show, Crabapple makes $45,000. The paintings were in her studio when I had the chance to visit last October and it was clear she’d been working on them for months before that. So that sum, minus materials, is for about a year’s work.

Forget the sniping.

The park is long gone. By now most of the energy that sustained it has dissipated as well. But when you look at one of these paintings, better yet at all of them, you can remember what it felt like. What it feels like. Take that energy onto the streets.