This is the second in a series of articles on Money and Movements. The first half of this article addresses some of the challenges of resource allocation and financial compensation in movement contexts. The second half of the piece aims to be solutionary.

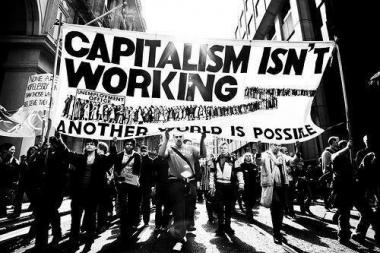

“These are the kids that did everything right,” Professor Stephanie Luce told the New York Times last month. “They went to school, they graduated and then they faced this very problematic labor market.” Luce was referring to participants in Occupy Wall Street, based on a study conducted on May Day, by the Joseph A. Murphy Institute for Worker Education and Labor Studies. Nearly a third of those surveyed on May Day had been laid off or lost a job, and so—given the large numbers of employed union workers one is likely to find at a May Day march—we can imagine that the true numbers of unemployed and underemployed everyday participants in Occupy Wall Street were probably much higher.

Youthful discontent often fuels movements; it's a cliche with basis. This time around, however, the youth leading the way were not necessarily current students. Many had already graduated, saddled with debt; others found the costs of an education too prohibitive to risk. Again, the study showed that a third of those surveyed on May Day were out of work even though 80% already had a Bachelors degree and 39% had a graduate degree. Many were clearly part of an emerging demographic of “educated people forced into unsteady or insecure jobs because little else is available”, increasingly known as the precariat.

When I first entered the job market almost 15 years ago, I was no different than the 20-something year-olds who led the way with Occupy Wall Street. I understood that in order to build my resume, I would need to do a few years' work as an unpaid intern. And I figured my media activism within the counter-globalization movement could help me gain the skills necessary to get a job as a radio journalist. I landed an internship at Chicago Public Radio and was a production assistant for a time, until I realized that media “objectivity” was not something I could pretend to believe in. By the time I was 23, I had hit my limit working for free. And what I really wanted to do was make change, not report on it from the sidelines. I decided I was ready to seek out paid work as a non-profit professional.

A few of my activist friends cautioned me against absorption into the NGO world, but I considered myself a realist; the often bombastic activist lifestyle seemed unsustainable in the long-range. And I admit, I was ashamed of doing unpaid work. I wanted to have the kind of credibility that opens doors. I wanted to be less easily dismissed, silenced or repressed – all things that activists endure pretty much constantly. Why surrender to the image of unpaid activists as filthy miscreants, arrogant enough to think they represent “the people” when actually they represent their own insular clubhouse? Especially considering that in contrast NGO workers are generally viewed as a clean, approachable professionals.

But more than all that, I assumed that people who argued against compensating people for their labor, must be entitled do-gooders.

I assumed that most people who work for free, do so because they come from a position of privilege, and a need to assuage their guilt through volunteer work.

I was not interested in being a volunteer. I wanted to work hard and get the compensation I deserved - and for me this was a form of self-interest rooted in a deep belief in interdependence.

Many youth who grow up thinking they will “serve society,” like myself, are reared on an idealization of NGO work. They develop an assumption that working in an NGO is probably the best way to strive for change, be effective, and get paid to do what you love at the same time. But, that's not necessarily the case. Because foundation support comes and goes over the years, even the “stars” of the NGO world often find the non-profit field a far from stable source of income.

More importantly, NGO space is not necessarily the space of radical change. As Andrea Smith writes in the introduction to The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, in order to garner funding, NGOs must frame everything they do as a “success”, and thus “become stuck in having to repeat the same strategies because we insisted to funders they were successful, even if they were not.” To retain support, NGOs must promote only their own work, and often undercut the efforts of the very people with whom they should ally (or merge). At its worst, competition between those who should be working with one another, turns cutthroat. At best, the focus on self-promotion for the sake of survival, creates a culture which “prevents activists from having collaborative dialogues where we can honestly share our failures as well as our successes.” In addition to creating a disincentive for honesty and reflection, skillshares and collaboration, the focus on self-promotion also forces NGOs to“niche-market rather than focusing on building a mass movement. We lose creative, innovative edge."

Think about it: Not a single major movement would ever have gotten off the ground if people were trying to meet the needs of their funders. Basically, if it were up to big donors, Occupy Wall Street wouldn't have had that “hot mess authority" which so mystified the media and held the public's attention long enough to shift the national conversation away from austerity measures to economic inequality. That's something NGOs had been trying to do for thirty years; after all those years of work, finally it happened in a few messy months.

Is working in non-profits about making change, or "making some change"?

When I was launching my career back in 2003, I was loathe to listen to the warnings of my activist allies. Like many people just starting out, I confused nonprofits with movements—and although sometimes movements are comprised of a constellation of non-profits, nonprofits and movements are not one and the same.

I ended up working for five years as a Communications consultant in Israel/Palestine -- which is the kind of place in which it quickly becomes clear that what is needed is not merely change, but radical transformation. Over those five years, I saw firsthand that every single one of the seven NGOs I worked for was far too mired in internal politics, to help build the kind of boundary-smashing movement that could bring about that kind of transformation. Across the board, the non-profits I was working for were so distracted by the fight for survival, that they were barely able to defend victories won by past movements much less make significant reforms or build a movement for radical change.

Professional changemaking as proxy

One of the ways that NGOs can actually impede movement formation, is by acting as a proxy for mass participation. There's this assumption that thousands of low-paid NGO workers can sacrifice themselves for us all.

It's a very North American kind of Superman or Christ complex.

Like MLK and Ghandi, our heros and saviors must not have normal lives. During their lives they must suffer like martyrs, and we expect them to die for our sins. (This is abundantly evident in the deep resentment towards the likes of Edward Snowden, a hero-figure who refuses to be martyred). Guilty as we feel about our inaction, we nevertheless rest assured that someone will save us from ourselves.

With our underpaid NGO martyrs, unconsciously, we think, “It's their job, not mine;” as if by donating money, we can pay a few people to make change on everyone's behalf. “A mass movement requires the involvement of millions of people, most of whom cannot get paid,” writes Smith,

“By trying to do grassroots organizing through this careerist model, we are essentially asking a few people to work more than full time to make up for the work that needs to be done by millions.”

Moreover, NGOs can discourage participation by unaffiliated individuals with valuable passion, perspective and skills to lend. Speaking for myself, when NGOs were forced to make cut-backs after the economic meltdown and I couldn't manage to find work in the social justice arena, I wasn't willing to offer myself as a volunteer, because stamping envelopes, handing out flyers, and phonebanking before D.C. marches once a year, tend to be the only options available in most NGOs. I knew the drill: when I was a Communications Director, volunteers usually took up significantly more of my energy than they were able to give.

The fact that NGOs often cannot offer significant ways for the unaffiliated to participate, is particularly problematic given the fact that "arguably, the most vibrant sites of radical and proto-radical activity and organizing against racist U.S. State violence and white supremacist civil society are condensed among populations that the (non-profit sphere) cannot easily or fully incorporate,” such as ad hoc movements, homeless people, undocumented workers, or incarcerated individuals. Because NGO volunteer coordination structures often fail to harness the energy of whole swathes of the population required to build a movement, in essence they can unintentionally exclude them.

And there's another piece to think through. Let's say you start work in a non-profit that works with undocumented workers, but you yourself haven't ever lived and worked without ID. You're going to get to know more than the average person about the challenges facing the people you work with. At the same time, as you join a professionalized activist class, you and your boss are going to constantly seek meetings with people in power, and/or 1% funders. You may be quite skilled at going between these two extremes, but that's exactly what you will eventually become: a go-between.

As a middleman and advocate you may unwittingly protect the people in power from the wrath of those whose needs they've failed to address -- we're talking about the kind of wrath that can catalyze movements.

You never know - dropping the intermediary, getting out of the way, could produce better results in the long-term.

Get your hustle on

Finally, there's the demobilizing–and erroneous–assumption that lack of money precludes action. “A fatal error made by many activists is presuming that one needs money to organize,” notes Smith.

“While fundraising is a part of organizing, fundraising is not a precondition for organizing”.

On the contrary, when people assume that funding is a prerequisite for action, it can become an impediment to movement building. This happens when people start to confuse sustenance of the movement with their own personal sustenance; leveraging their participation in a movement in order to support themselves, they begin to consolidate power as a step in the self-promotion process, competing with those they should cooperate with, for limited jobs. Occupy Wall Street came about as a movement specifically to challenge the consolidation of power in the hands of those with disproportionate control over resources. In such a movement, prefiguratively addressing internal allocation of money and other resources was of vital importance. And aligning principle and practice was going to be an organic process, and it was going to take a while.

But meanwhile, the world was going to end in 2012, remember? The sense of urgency was incredibly palpable, and there was so much work to do. So some of our most seasoned activists jumped into action, courting funders directly and establishing spin off organizations. But there was an unintended consequence: while their organizations dreamed up and executed fruitful campaigns, they did not become “the movement”. In fact, some of those firebrands actually became somewhat isolated from movement-building work.

“You get what you design for,” says Monica Sherpa, a former United Nations consultant who helps visionaries realign their practice with their guiding principles (and who mentored a few Occupy activists). Distributing or taking money before a structure for distributing money is developed, creates a non-transparent resource distribution structure. If you don't have transparency built in, nontransparent structures will organically develop and eventually become isolated from the whole. This is why it makes practical sense to continually ask ourselves if we are aligning our principles with our practice. If we don't grasp this, how can we challenge the lies and the hoarding of the 1%?

We need to engage in serious conversation about the impact of paying people in a movement scenario, because the question of money–especially in the fight for economic justice–will never stop coming up. Hustling to making a living, can really kill movement spirit.

And working in a non-profit easily becomes less about making change, than about “making some change”.

THE SOLUTIONARY PART: Making A Living, Without Killing Your Spirit

“I understand that you're broke. I've been there,” I whispered over a tiny table in a Jerusalem cafe, “but I am surprised that you're asking this question yet again.” Just a month earlier, a new volunteer had flown all the way from New Paltz, New York, to “help” our small grassroots NGO, and this was the third time I found myself explaining that we did not have the money to offer her a paid position. I myself had been hired just six months earlier, to transition the organization from a volunteer-powered direct action movement, into a small non-profit organization with three paid staff. “Why do you think we meet in cafes?” I pleaded. “As you can see, we don't even have enough money for an office.” This time she seemed to be getting it. “Look, in New York, for a year I couldnt find work,” she admitted. “Me and my friends always talk about how it's all about getting your hustle on. I guess I was desperate enough to come all the way to Israel to get my hustle on."

When I found myself in New York City a few years later, I started to understand what she was talking about. In this city full of bustle, all of us, without exception, have to look out for ourselves and get our hustle on. But even while hustling, there are ways to work with each other; we don't need to compete for limited scraps within the same occu-pie.

In the previous section, I summed up some of the challenging questions that arise when the question of payment comes up in a movement scenario:

Not everyone can get paid. (Which leads to the question: When not everyone can get paid, how are decisions about who will get paid, made?)

None of us can do it alone. (Choosing a few paid staff shifts work that should be done by thousands, onto the shoulders of a few very stressed out people.)

Protecting one's position is only natural. (When people are paid, they're going to want to continue to get paid, and they're generally going to do whatever they can to make sure that happens.)

Payment source = the source of power. (Those who are paid, answer to whoever pays them, consciously or not, officially or not.)

The purpose of this article, however, is to suggest alternatives to working in NGOs alone, or to creating NGOs within a movement context. If what you really want to do, is to make real change, then you don't want to do something thats against your values, and you don't need to. You can create a flexible worklife for yourself that enables full-on engagement in social change work.

Work for yourself: Become an entrepreneur.

Assume that it will take at least 6 months to market the business and make the connections you need. Plan for a year of being dog-tired as you build it up. Two tips:

*Businesses with less overhead (rent, supplies, etc.) will be less risky. For example, I have a dogwalking business, and it cost me maybe a few hundred dollars in rain gear and business cards, so if the business failed I could simply head in a different direction without any real losses.

*You may want to run two shows at once, so that if one takes longer to build up than the other, you still have a source of income. As I transitioned from the Middle East to New York City, I offered my Communications skills, pro bono to a range of organizations; I got calls for work years down the road when funding was available. Working pro bono, while operating a dogwalking business, I was able to pay the bills no matter what came, and when business was good, I saved.

Work with others: Get cooperative.

The most practical, stable cooperative models I personally have encountered, also leave the most room for autonomy. Here in NYC, you have the cleaning co-op, Si Se Puede. Another model that has worked elsewhere: an anarchist dogwalking collective, or joining forces with other dogwalkers to start a co-op once your business is stable.

Then there's the amazing model offered by Cafe Chicago, a fair trade coffee roasting and bean delivery co-op with high profit margins. The model is decentralized, and designed to support social justice ventures in related arenas. It's up to each individual to roast their own coffee, create and market their own label, develop their client base and deliver it to them. So that no one takes over the business or creates a monopoly, no single entrepreneur can make this their full-time gig – they have to have another source of income. This kind of co-op offers a lot of the autonomy that comes with having your own business, and the sense of community gained from working with others.

If you need money soonish, and are considering joining that long tradition of coffee shop, restaurant, print and grocery co-ops, consider that they tend to require a lot more of a long-term commitment and take longer to become profitable. Speaking as someone involved in a well-loved collective coffee shop for three years, these types of co-ops, are all-consuming and will leave you next to no time to engage in other types of activism.They will consume all your time and devotion in the early days, and if they are to succeed they will require a willingness to sacrifice, as they take a few years to make a profit. At the same time, if you start a co-op without the aim of making a “profit” that gets redistributed equally to all the workers, then don't bother. When co-ops “make it”, it's because they are practical, profitable places to work – the work is manageable, and they pay the bills. (Anyway, co-ops alone, in the capitalist world we live in today, will not solve the “problem of capitalism” on a wide economic scale.)

Starting any old co-op will not be a quick fix to your financial problems. Study up on cooperatives – they are not all the same! No one model will work everywhere, so think this through, get some some guidance, and commit for the long haul.

http://www.uwcc.wisc.edu/howtostart/Resources/

http://www.cdi.coop/usefulinfoandlinks.html

http://www.ncba.coop/ncba/about-co-ops

Startup loans in NYC: http://www.theworkingworld.org/us/where-we-work/new-york/

Get a job. (But set the terms)

Maybe you're the kind of person that doesn't want to work according to consensus process in your daily workspace. Maybe you think you can get more done in a hierarchical structure, and you want a supervisor or a boss to give you some work to do, and approve the results. And maybe you're ok with contributing your skills towards reinforcing the integrity of a vision not your own, but which you believe in or support. Certainly, if you are forwarding someone else's vision rather than your own, that means you are going to take direction from them, and you're going to want to get compensated.

And, let's be real -- in a place like New York City, where the first question out of any stranger's mouth is often, “What do you do?" -- maybe you want to have a job you can describe easily. Maybe your family puts a lot of pressure on you and you don't come from a particularly lefty community; you want to make mom and dad proud and you want a job your friends will approve of. It can be tough living on the margins.

If “fitting in”, or taking direction, in one area of your life, will free you up to be wildly innovative in the space of activism, by all means do it. But be aware: you may unconsciously begin to self-censor some of your more creative and innovative impulses, if you fear that those that pay you will be disinterested in, or disapprove of them. And let's be clear: if you are paid by someone, you are ultimately more likely to answer to them, than to the community. So just be sure to take a moment to be honest with yourself about the limits and potentials of whatever arrangement you set up, and check in with yourself regularly, ask: “am I still my own master?"

*Working for the man.

Back in the day, committed labor organizers often dropped out of university to join the “working class” and agitate from within. It's a privilege to drop your privilege, and probably not what “the oppressed” really want from you. At the same time, unless you've worked for “the man”, you can't begin to pretend to know what most workers in this country are going through. There's something to be said for working for “the man” (especially because most activists get pretty out of touch at the height of planning actions). Are you hanging out with your “vanguard” too much to relate to what life is like for 99% of the people you're fighting with and for?

Occupy Wall Street operated in a way no working person could actually participate in – especially if they had dependants. I know that after working a full day, the amount of time some meetings took, often felt like an insult; I would often think, If this feels like an insult to me, what about working people with kids, a family to support? How were we supposed to be a movement for the 99%, a participatory movement, when decisions were being made and refined and reversed on a 24:7 hour basis, and actions were never planned more than a week ahead? I am quite certain that if more of us had work-lives like the 99% we were fighting with/for, far less decisions would have been made for them—by full-time activists holding ad hoc, closed meetings. We lost thousands of amazing people by operating this way – totally out of touch with the realities confronted by the 99%.

*Working for an NGO.

So you've considered all of the above, and you've still decided to take a job in an NGO. It can be done, but be smart and communicate clearly, establish clear boundaries and expectations, so that you can engage in work outside the scope of your job, with freedom. Some people in the early days of Occupy Wall Street had frank talks with their bosses and were able to work out arrangements necessary so that they could participate in building a movement beyond the bounds of their finite NGO structure. It's crucial to establish boundaries and be transparent.

-When you work for an NGO or union, and go to a meeting, you represent that organization. When you speak, you can't always say exactly what you think (especially about the organization you work for). And what you do can often reflect on the organization, even once the day is over. So your boss needs to understand: When clocked out, in public, you represent yourself, not the NGO, and you need to represent yourself that way if you talk to the media as well. Clarify: When does your paid work start and finish? Who do you represent?

-If you are with an NGO or union, best-case-scenario, they will pay you to work in coalition with other groups. If there is crossover between your paid work, and your unpaid work, always be transparent about it. Disclose: What's your affiliation? How will this influence what you are, and are not, able to say or do? (Do this briefly every time you notice people new to a particular meeting space).

Holding your ground

Now, whatever our internal and external challenges, Occupy Wall Street has something special about it, don't you doubt it. And we do something different than most of the movements we are allied with. What do you think that is?

We create and hold space for the unaffiliated. And we need to hold our ground and keep doing that. In a meeting full of NGO representatives, each person stands for dozens, if not hundreds or thousands of people.

At a lot of NGO coalition meetings, a nanny, an “unorganized” laundry worker, or an independent contractor has no place; they are not going to feel included, or feel their power, in such a space.

In effect, just by representing their organization, NGO and union reps can unintentionally disempower the unaffiliated folks present at a meeting. So don't play that role! Know your own power, represent yourself and yourself alone.

No one asked me, but here's my advice to young people just starting out in this country, 10-15 years my junior: Don't drink the commodification cool-aid. Don't believe that your value is quantifiable, tied to making money in any way. You need money to eat, that is all. You don't need money to make change and you don't necessarily need money to accomplish great things. And above all, to make change, you need the freedom to create. You need lots of people to run with and build smart strategy. You need space to get angry, to have fun, and to see what you can do with the material you have.

The takeaway could not be simpler: If you really want to build a movement, don't leverage your participation in the movement to support yourself.

Seek work to support your continued participation in the movement, like many people have done before you, and will continue to do after you. Above all, it's about being creative. And it's about being your own master.